Business & Money

A few days ago there was an announcement that Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JPMorgan Chase are creating a joint healthcare venture. The press release is pretty vague, but intriguing nonetheless.

To start, let’s look at AWS to get an idea of how the Amazon model works. As Amazon was scaling in the mid-2000s, it decided to build an easy-to-use interface that developers across the company could use to spin up cloud servers, build applications, and access the necessary compute and storage resources as-a-service. And once this system got to scale internally, it offered the whole thing as-a-service to external developers. So now anyone in the world can leverage the front end that Amazon has built (aws.amazon.com), leverage all of the back-end technology (servers, data centers, etc) to deploy whatever app they’re working on far faster and far cheaper than would otherwise be possible.

It’s the same story with e-commerce. Want to sell something? Leverage the interface at Amazon.com and all of the back end tech (fulfillment centers, logistics networks, etc) to be up and running in no time.

So I imagine this will be the plan for healthcare. Build a front-end interface for Amazon employees (and those at Berkshire and JPMorgan) to easily access insurance information, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacies, and any other players in the ecosystem, while also building the back-end infrastructure to make the whole thing possible. And once they have that figured out, of course, open the floodgates by offering that same interface+infrastructure to other employers and maybe even individuals at some distant point in the future.

The really interesting thing to me is that, while this is all playing out, all of the healthcare suppliers (insurers, pharmacies, etc) will likely be modularized in the process. If Amazon becomes the front end, then it won’t matter to the consumer what insurance company is behind the scenes paying the bills or what pharmacy fills a prescription. And I think it’s this idea that explains why healthcare stocks across the board sold off when the announcement hit the wire. The writing is on the wall.

Now if this hypothetical scenario does play out, it would do so over a very long period of time. Maybe 10, 20, or even 30 years. So the short-term selloff is likely a bit of an overreaction in the immediate term. I imagine short-term traders are taking advantage as we speak.

But speaking of how long this will take, I think that explains why the aforementioned companies are partnering on this initiative. Nothing I’ve mentioned to this point requires anything from Berkshire or JPMorgan. The strategy, approach, and time horizon is purely and quintessentially Amazonian.

However, Berkshire brings something interesting and unique to the table. While they do not play in healthcare insurance directly, they are one of the largest reinsurers in the game. That is, they provide insurance for the health insurance companies. So they wouldn’t be at risk of being modularized by this new platform, but would instead provide a vital piece to the puzzle.

And finally, we have JPMorgan. What are they doing here? Well, one of the lines from the press release says that the new venture will be “free from profit-making incentives and constraints.” First off, I think it’s highly unlikely that these guys are building a non-profit (if you disagree, I’d love to hear your perspective). Instead, I think that sentence reflects the long-term perspective of the partnership. This won’t be a money-making endeavor anytime soon. If they can be successful with this, and that’s a massive IF, this will take many many years and many many dollars to unfold. And as such, access to capital markets and financing will be a critical component to the long-term strategy. And who better than JPMorgan to fill that role.

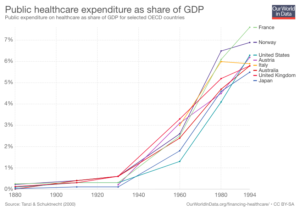

Human Progress

The sharing economy fascinates me. It’s incredible how, over a very short span of time, entrepreneurs across the globe have identified ways to better utilize and monetize existing resources.

On the employment front, this brings many new and exciting opportunities to the table. Workers have a new found flexibility to define the nature of work for themselves. Individuals that may have otherwise had limited opportunities can now easily become market participants. And sharing economy platforms generally have the ability to scale in a way that traditional businesses cannot (low fixed costs, network effects, etc). As such, the net benefit to job creation can be massive.

That said, the moral and ethical implications are also significant. There is a chance that workers become completely commoditized by these platforms. When you think of a company like Uber, it’s hard not to think about the low bargaining power of drivers which leads to serious exploitation. We’ve all read about how drivers can be penalized for shutting off the app, the gamification elements that lead to long hours, and how long it took to get tipping implemented. And given that sharing economy laborers are often contractors (as opposed to employees), their ability to collectively bargains is basically non-existent.

So how can we ensure that we benefit from this incredible new business model, without allowing the negative externalities to run amuck?

To start, I think it’s important to think about how the reputation systems are employed. All sharing economy platforms use them, but all are not created equal. For example, let’s look at Airbnb. If you’re a host with great reviews, your listing gets prioritized in search results and you have the opportunity to make more money. So the platform leverages the system to create more economic opportunity for participants. Uber, on the other hand, leverages their reputation system to remove bad actors. I can’t find any evidence that higher rated drivers are more likely to get more fares. Instead, as long as your reputation is high enough to remain on the platform, you are matched based on location and pick-up times. What if riders could see these rating ahead of time and select drivers based on them? That small change might provide more incentive for safe driving and better reward the top drivers on the platform with more fares and more money.

Another thing to consider is whether these platforms encourage repeat transactions between the same buyer and seller. For example, when I was running DogsterApp, I used LawTrades as my platform for legal services. It matches you with qualified lawyers based on what services you need. And when you find the right lawyer, you can basically pay a flat monthly fee for a block of that specific lawyer’s time. It’s like a dedicated and on-demand general counsel. And over time, I can build a relationship with a specific person based multiple interactions and trust. I think this encouragement of repeat transactions between the same people empowers suppliers (the lawyers in this case) to build reputation, a loyal customer base, and again, increases their earning potential. Contrast that with platforms like TaskRabbit where you are just matched with a different random person each time you use the platform. The latter leads to commoditization of labor and exploitation, just like the Uber drivers.

Finally, I think the ability to set the price has a lot to do with the quality of the experience for workers on these platforms. For example, you can use a platform like Thumbtack to secure local services like house cleaning or carpentry, and the workers have the ability to offer their services at whatever price they decide. That type of flexibility allows greater freedom and agency for suppliers, while not allowing the platform to control their earning potential.

These are just a few things to consider, but perhaps we need some form of regulatory checklist by which to evaluate the merits of these platforms and determine if they will produce a net benefit to society.

Philosophy

For the longest time, when other people would speak, I would always listen with the intention of replying. As I took words in, I was simultaneously figuring out what I was going to say next in response. And it makes logical sense. A conversation is an interchange between two people wherein they take turns speaking.

And in sales, it seemed to make even more sense than in normal conversation. When an existing or potential customer speaks, it’s often about why their current situation is working and why they don’t need any help. It’s about how they made an investment with a competitor and their needs are being met. So logically it was my job to find cracks in the story, respond with how our feature set was superior, or elicit fear, which might encourage them to make a change.

But at some point, in both work settings and my personal life, I made a change. I stopped listening with the intention to reply, but rather listening with the intention to understand. I mean really understand.

And funny things happen when you make that change.

First, the pace of conversations tends to slow down. There are often pauses after the other person stops speaking. And I think that’s a good thing. It makes conversations more thoughtful, deliberate, and insightful. (But the silence does take some getting used to.)

Second, I found that my replies, more often than not, would be another question, rather than an answer or statement of fact. Because in reality, only so much can be said with a couple sentences. Word choice matters. Tone of voice matters. Body language matters. And when you really listen and make a genuine attempt at understanding, you start to get curious about why a person uses one words versus another. You start to get curious about what underlying emotions and drives might be coloring the conversation. And everything in life really comes down memories and motives. To past experiences and future desires. The more you can understand those things, it seems the better you can influence or motivate a desired action.

And finally, you end up with deeper and higher quality relationships, whether business or personal. And things basically boil down to relationships, so this seems to be a good outcome.

My Latest Discovery

Last week I touched on the fact that many companies have been giving out these one-off bonuses in response to tax reform. And every example that I had seen to that point was basically the same. Here’s a $1,000 bonus check, spend it wisely!

But this week, I stumbled upon a press release from Hostess.

“Hostess Brands, Inc. today announced that, following the recently enacted tax legislation, the snack cake maker will be providing bonuses totaling $1,250 to its 1,036 hourly bakery and corporate employees. The bonuses will include $750 in cash and a $500 401k contribution.”

I love the 401k contribution angle. Think about it. For hourly workers in retail or manufacturing, there’s a fairly high likelihood that they might not be the most highly educated employee base. And as such, a $1,250 cash infusion might fly out of their checking accounts just as quickly as it arrived.

This is a great example of long-term thinking from the executive team at Hostess and real investment in its people. Good Stuff Hostess! (That doesn’t mean I’ll be eating any of their manufactured poison anytime soon)

Like this:

Like Loading...